It has been proposed that America’s essential contributions to world culture boil down to jazz and the martini. If the latter is true (and who am I to argue against it?) then gin—the beating heart of a true martini (emphatically not vodka)—has become a true American spirit. One look at the current Northwest gin scene would seem to cement the case.

Though the medieval origins of gin are cloaked by the centuries, today’s Northwest distillers are honoring gin's past while pushing the gin genre forward with innovative rifts on classic formulations. They are even helping define an entirely new category of gin: New Western Dry Gin.

“Gin is always built around juniper as its forward flavor,” explains Ryan Magarian, bartender extraordinaire and long-time spirits and cocktail consultant who coined the term New Western Dry to describe this emerging gin style. “But around 2005, some folks in the Northwest became captivated by the idea of taking creative license in the gin category. Some of us wanted to explore how much balance we could achieve between the many botanicals that are typically used in gin, and the core juniper flavor that defines what gin is.”

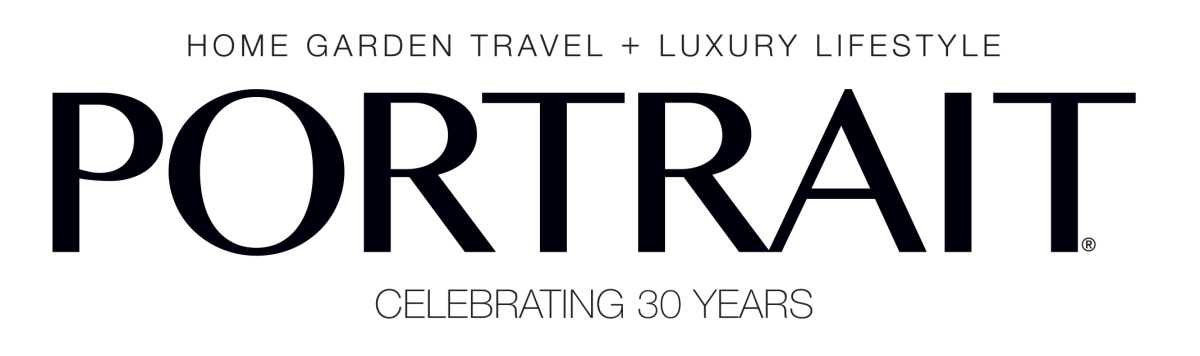

A seminal result of this work was the creation of Aviation Gin, a collaboration between bartender Magarian and distiller Christian Krogstad at Portland’s House Spirits Distillery. While not the first gin to push the boundaries of traditional recipes (Tanqueray and Hendricks were some of the earlier examples), Aviation Gin was the first American made, artisan-crafted gin of this style to achieve national market acceptance.

As Magarian points out, their timing was impeccable. Aviation was introduced just as the craft cocktail renaissance was gaining momentum, and this new gin’s more balanced flavor profile—Magarian calls it a “democracy of botanicals” rather than a “dictatorship of juniper”—made it popular among cocktail crafters. Named after a classic pre- Prohibition-era gin cocktail, Aviation’s flavors have a juniper nod to the classic style, but also evoke the Northwest with a sense of earthiness and mountain air, with a light citrus touch. Its success helped inspire a raft of other Northwest distillers to forge their own gin paths.

Sometimes the path to the future lies in the past, as Tad Seestedt, owner and distiller at Ransom Spirits in Sheridan, Oregon, discovered. Attracted by the myriad aromatic possibilities in gin, Tad began looking at London Dry recipes about the same time Aviation hit the streets. This is globally today’s most popular gin style, emphasizing forward juniper flavors and a dry and crisp character— accenting botanicals playing strictly a supporting role.

But why, friend and cocktail historian David Wondrich wondered, tread such a well-worn path when there were older gin styles in need of resurrection? Old Tom gin, Wondrich proposed to Tad, was a gin ripe for a revival. Old Tom is a stylistic bridge between the original proto-gin called genever (or Holland gin) and today’s fresher-tasting dry gins (London or New Western gins). It has a more malty flavor and heavier body than modern dry gin, but less of the sweet and densely malty character of the original Dutch genever. Throughout the 1800s, Old Tom was the gin of choice until it died a quiet death in the 1950s.

Tad took up the challenge and with Wondrich embarked on creating an historically accurate revival of this staple spirit of the golden age of American cocktails. “It was a big learning curve trying to faithfully recreate Old Tom,” says Tad, “but it also deepened my understanding of gin and helped me create our other two gin styles as well.”

Based on malted barley, juniper, citrus peels, coriander seed, cardamom, and other botanicals, and then aged in French oak wine barrels for three to six months, Ransom’s Old Tom is an entirely different—and delicious— sort of gin. “It has the intense aromatics of a more modern dry gin, but also a more malty, richer, almost—but not quite—sweet character,” says Tad.

Again, the timing was good. Released in 2008, Ransom’s Old Tom was the first modern American-made gin of this style, appearing a scant year after England’s last producer of Old Tom re-introduced their Hayman’s Old Tom Gin. Ransom caught the wave and, like Aviation, became one of the darlings of the national cocktail craze.

Northwest gin success doesn’t always have to mean pioneering something new or resuscitating something forgotten—it can also mean polishing a classic until it shines.

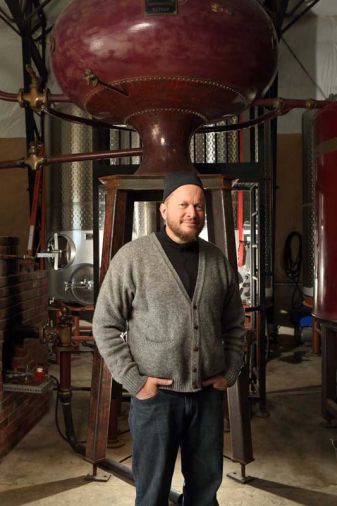

“Historically, gin has always evolved,” says Ryan Csanky, co-owner of Aria Gin in Portland, “and I really love that Northwest distillers are pushing the gin envelope.” Initially Ryan and his partner Eric Martin thought they’d go in that direction too. But with years of experience behind the bar at Portland’s iconic Wildwood restaurant, Ryan began itching to produce a more classic, mixable gin.

“A lot of the new-style gins, as great as they are, don’t always work as well in classic cocktails as I would like,” he says. As they tasted around the market, what Ryan and Eric did not see was anyone regionally making a true London Dry style of gin. So they did it themselves. They wanted a gin that appealed to the traditional gin palate—juniper forward, crisp, dry, citrus edges—but also a gin that had its own identity.

“We wanted to create a gin with a classic sensibility but without trying to imitate someone else.” Using a selection of ten traditional gin botanicals, Ryan and Erik took four years, and hundreds of individual distillation trials, to come up with the Aria formula. Once they did, they were ready to launch and on October 11, 2012 they sold their first bottle—even before the inaugural bottling run was complete.

Aria is currently made in small pot still batches at Bull Run Distilling in Portland (though later this year Aria will open their own distillery and tasting room) using only raw natural ingredients; none are added after distillation and no essential oils are used. “For me, it’s all about balance,” says Ryan. “It makes for a gin that is approachable for people who like and want a traditional style, yet it has turned out to be equally approachable for people who say they don’t like gin.”

Today’s Northwest gin scene is growing ever more complex. If you think you have a handle today on who is producing what style of gin, just wait a month or two and the landscape will have changed.

Oregon got a jump on the Northwest craft distilling scene in the mid 2000s when distillers like House Spirits and Ransom began gaining national attention. But Washington quickly followed. Dry Fly Distillery in Spokane launched in 2007 and co-owner Kent Fleischmann was instrumental in getting the state legislature to open up the state’s regulations, allowing for a rapid expansion of Washington spirits producers. By some accounts, Seattle now has more distilleries than any other city in the country.

But is there a definable Northwest gin style? Ransom’s Tad Seestedt doesn’t think so. “Our industry is still so young at this point that I don’t think we’ve had enough time to develop a purely regional style. If there were, it would come from using predominantly botanicals that are grown in the Northwest—and here there are perhaps great opportunities.” Ransom does use marionberries in their Dry Gin, and Tad has experimented with hazelnuts. Still, of Ransom’s three gins, it would be hard to call any of them truly “Northwest” in style.

When Ryan Magarian and Christian Krogstad were working to create Aviation, they succeeded in crafting a spirit that reflects the flavors of the Northwest—yet there was nothing specifically Northwest about their ingredients. “It’s really cool that the Northwest has been a leader in craft spirits,” says Magarian. “Some people try to add something to give their product a Northwest profile, sometimes in an effort to establish their own identity. We’re lucky enough to live in this petri dish called the Northwest where a freewheeling culture allows craftspeople to try new things—for better or worse.”