There is an old Italian saying, “Grow grapes for your children and olives for your grandchildren.” Olive farmer and miller Paul Durant echoes this sentiment as he weaves between rows of ten-year old Arbequina trees, a hardy Spanish variety of Olea europaea. He squints into the spring sunlight that his young trees bask in, as he explains that olive trees can take up to 40 years to reach full maturity—one reason for the timeless adage.

Olive trees are rich with lore and legend, in ancient Greece, the tree was considered sacred, and a symbol of life, wisdom and prosperity. When rooted in the right place, they thrive, and live for hundreds—even up to thousands of years. The cultivation of olives trees, and extracting olive oil, dates back over 6,000 years, and is also steeped in mythology. Poet and author Homer deemed olive oil “liquid gold.”

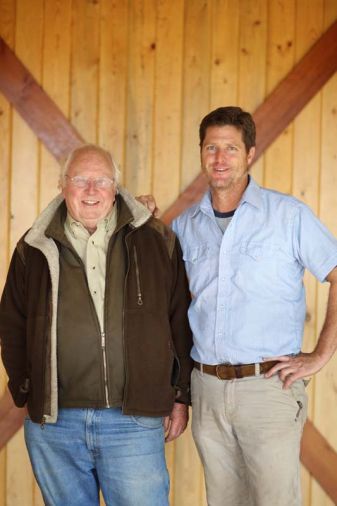

“I’m working with an ancient crop with significant cultural ties— that’s one reason why I love to do this,” says Durant. The historic home of the olive tree is the Mediterranean, but farmers now tend to groves across the globe from North and South America to Australia and New Zealand. Paul and his father, Ken, planted 11,000 olive trees in Oregon in 2005 as a grand experiment. The rainsoaked Willamette Valley is far from a Mediterranean climate. But, why not try?

“My parents are entrepreneurs at heart,” says Durant. They are also pioneers, willing to take risks, and eager to innovate. In 1973, Ken and Penny Durant planted one of the first vineyards in the valley—when the surrounding farmland was a patchwork of wheat fields and orchards. “They started with three acres of pinot noir, chardonnay and riesling grapes,” says Durant. His father was a hobby winemaker, and planned to sell most of the grapes to aspiring winemakers.

At that time, the idea of grape vines in the Willamette Valley prompted older farmers to chuckle. Today, the Durant vineyards stitch through the center of Oregon’s premiere wine region in the famed Dundee Hills. And the three vineyard acres have prospered to over 60 acres, with most fruit still sold to neighboring winemakers, and a small amount bottled under the Durant label.

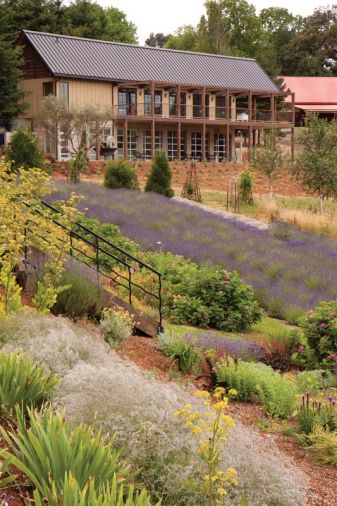

“My mom is of Irish descent and land is a great passion of hers,” says Durant. Plus, he quips; neither parent likes to sit still. This led to the debut of their destination plant nursery in 2000, Red Ridge Farms, where they sell aromatic herbs, specialty plants— like olive trees, and artistic outdoor pottery.

With multiple businesses flourishing, the olive oil venture required a dedicated lead. “I’m the humble implementer of my parent’s vision,” says Durant. In 2010, he left his career as a mechanical engineer to return to his family’s 120-acre farm fulltime. Tall and lean, sporting farm boots and faded denim, Durant grins when he recalls that decision. “This is where I’ve always wanted to be,” he says. “I grew up in these vineyards,” he says. “It’s such a beautiful place.”

On a clear day, like today, when Durant walks the olive grove, he can spy the snowcapped peak of Mt. Hood gleaming in the distance. Elegant vines etch across nearby hillsides, and newly crafted wooden bee boxes cluster near lavender bushes. (Estate honey is next on the list). More than thirty years later, his daily footprints trace the same path his parents did back in 1973. He’s following their lead, taking a leap of faith in farming—a pursuit that requires patience, persistence and passion for the land.

Any new venture is not without challenges, and one that Durant embraces with the curiosity of a scientist, is the agronomy—playing matchmaker with the tree and the climate. The biggest question he’s faced: What coldhardy olive tree can survive the occasional freezes the farm encounters during the winter? Over the years, the family has run tree trials—and handpicked several varietals for their site, including the Spanish Arbequina and Picual, and several Tuscan cultivars.

Mother Nature, though, is not known for her predictable nature. And neither is the Willamette Valley. Durant crests a slope, reaching a row of Arbequinas similar in age, but vastly different in size. One tree bursts with the signature silvery-green leaves, the adjacent tree is mostly bare and struggling—it did not fare as well this winter. It’s one of many puzzles that Durant must decode. “We have found a path,” he adds, with positivity.

Durant strides past a tractor, ducks under a garland of wisteria and sidesteps into a humid greenhouse, rich with the aroma of earth and herbs and blossoms. “This year, we plan to propagate our own trees,” he says. An idea that struck after a bonsai master (who cultivates bonsai olive trees) visited the mill. “It’s just like when my parents got cuttings from winemaker David Lett over thirty years ago,” says Durant. He carefully plucks and then cradles an olive tree cutting the size of a butterfly in his hand. A mosaic of cuttings in tiny seeding containers quilts two wooden tables. Each slivery sprig a symbol of hope.

In five short years, Durant has fast-tracked in an industry with longstanding traditions. He’s a certified master miller and has taken charge of the entire Oregon Olive Mill production. The compact facility includes the mill and production area, a bottling line, and an oil storage area. This gleaming space was home to the first olive pressing mill in the state of Oregon, and is the only estate olioteca in the Pacific Northwest.

When the family purchased their small Italian olive mill, the manufacturer sent over Duccio Morozzo della Rocca, a master miller, for two seasons. Durant learned about the craft of olive oil blending and state-of-the-art milling techniques from the Italian master. “What was most memorable was learning about the cultural connections to olive oil,” says Durant. One of the rituals the family took to heart from the master miller was the tradition of the Olio Nuovo Festa in Italy, where millers and producers swing open their doors and invite the community to taste the freshly pressed, new olive oils from the harvest.

Olio Nuovo is the freshest extra virgin olive oil you can find—it has a deep green hue, and is full of rich sediment from the milling process, which adds texture and flavor. On the palate, the oil is peppery and fruity with a burst of freshness. The longevity of oil is fleeting—with a limited shelf-life, it must be used within a few months. Last November, Oregon Olive Mill hosted over 1,500 people during their fifth annual weekendlong festival. In the spirit of tradition, they also provide milling services

to other olive growers in the area.

“I love milling, especially when the fruit comes in,” says Durant. “The fruit usually arrives at night, so it’s kind of like Christmas. You have a big truckload of olives, and you never know exactly what you are going to get.” Currently, the Durants harvest olives from their 13,000 trees, and augment their crop with olives brought in from family farmers in Northern California, producing small batches of blended olive oils. In 2015, the family will celebrate their eighth year of making olive oil in Oregon.

Durant is often asked about producing olive oils made with 100% estate fruit. Part of the challenge stems from the young trees growing enough fruit, the other—predicting and prevailing over the whims of Mother Nature. “Realistically, if we have a bad winter, and a crop failure, it would be devastating to have no olive oil to sell,” says Durant.

He does make a very limited quantity of estate olive oil, a project requested years ago by chef Vitaly Paley of Paley’s Place and Imperial. “As a longtime supporter of all things local it only makes sense that Paul’s olive oil plays a big part on our menu,” says Paley. “But the real reason is that it is one of the best oils I have ever had,” he adds.

The chef uses the olive oil extensively at both of his restaurants to finish most dishes including all grilled and sautéed items as well as the house made charcuterie. “Personally, I like dipping some crusty bread in it and eating it as is with just a light sprinkling of salt,” he says. The Oregon-made olive oil also graces many wine country restaurants, and unexpectedly, can be savored by the scoop at Salt & Straw, where the extra-virgin Arbequina Olive Oil ice cream was named one of Oprah’s favorite things in 2012.

Just as his parents forged a path in the nascent wine community, Durant aspires to establish an olive oil culture in the Pacific Northwest. That’s why he’s spearheading an annual Pacific Northwest Cool Climate EVOO (Extra Virgin Olive Oil) Conference, where he brings together chefs, olive oil experts, authors, scientists, importers, and growers from across the west coast. This year, the mix included Nancy Harmon Jenkins, author of the recently published Virgin Territory: Exploring the World of Olive Oil.

As she spoke about her book and her travels, Harmon said: “Food is a way of telling stories, about what we believe in, and it’s the the quickest route inside another culture. Which is one of the ways that I came to olive oil.” The story of olive oil in Oregon is just now unfolding. It’s a new frontier. And similar to our wine, olive oil evokes a distinct taste of place—whether it’s green and grassy or robust and peppery—we get a sense of the seasons, the sunshine and the rain that is Oregon.