It’s late Autumn, and we are on the hunt for culinary gold—Oregon truffles. Elusive. Beguiling. Fleeting. Just a few of the terms used to describe the captivating mushrooms, coveted for their umami essence.

The morning begins chasing Christopher Czarnecki, a fourth-generation chef and restaurateur from the Joel Palmer House in Dayton. Past sleepy, bucolic towns of the Willamette Valley, up gravel-strewn roads into the forested hills above the Valley we follow his license plate, which reads: Fungi. He leads us to a private Douglas fir forest, draped in a garland of wispy fog. I find myself standing at the edge of the forest with Vitaly Paley, the chef-owner of Paley’s Place and Imperial Restaurant in Portland and one of the pioneers of farm-to-table dining in the Pacific Northwest. Today is the first truffle foray for us both, so we listen for tips, and zip up raingear before venturing into the Tolkien-like terrain.

The three of us stalk across ochre pine needles and over moss-drenched tree roots. We are deep in a Douglas fir forest where the air is soaked with the scent of pine. A wispy fog garlands the evergreens, adding mystique to our hunt for buried treasure.

“The first sign I’m looking for is animal activity,” says Czarnecki. We scan the damp earth for holes around the base of a tree, where scurrying moles, voles or squirrels stash the coveted edible riches. He pauses, “something was definitely just digging right here.” The chef leans forward and lightly scratches the duff from under a Douglas fir tree with a four-prong garden rake. With the softest touch, chocolate earth crumbles toward our rubber boots.

“Infectious isn’t it?” muses Paley, who, like Czarnecki is eager to unearth culinary gold this morning.

Chefs prize these jewels of the forest for their umami essence, and ancient lore proclaims this earthy fungus an aphrodisiac. “They can, on certain occasions, make women more tender and men more lovable,” wrote Alexandre Dumas.

Small but precious, truffles are spore-bearing fungi that live their entire lives underground. Animals such as grey squirrels and chipmunks dig up and eat the truffles, serving as the main dispensers of its spores. Oregon truffles develop in symbiosis with trees, and grow throughout the Northwest in low-elevation Douglas fir forests, from northern California to southern British Columbia. The fungi thrive in semi-cultivated environments, places like this. Tidy tree trunks surround us, reaching up to the sky as straight as arrows. A growing pattern indicating this forest was once a Christmas tree farm. “It was intentionally planted and that’s the environment that the truffles like,” says Czarnecki.

Of the 30 Northwest truffle species, only three are harvested for culinary use—two whites and a black. We are in pursuit of the winter white (Tuber oregonense). At its peak, the white truffle carries aromas of earth, herbs, garlic, and an almost petrollike note. The provocative fragrance is just part of the allure. As British author Elisabeth Luard writes in her book Truffles, part of the magic of the mushroom is how it evades us: “Let me put the case for treasuring the truffle. Leaving aside culinary considerations, the truffle is not just a fragrance, a flavor, a face—though all these things contribute to its allure—it’s a nugget of vegetable matter searching, as must all living things, for a niche in which it can thrive. And its niche is remarkably specific. Let one thing fall out of line, and the whole enterprise falters and fails.”

Taking her words to heart, we change direction in the Tolkien-like terrain, skating across moss and fallen leaves to cover new ground. Standing about ten feet apart, we each cast our rake across a bed of fir needles, and pray for mushrooms. “Sometimes you find them right away,” says Czarnecki, “other times they make you really look for them.” If you find one truffle near a tree, you’ll usually find more, he adds. The chef sweeps the soil a few times before sidling up to the next tree. Across the path, Chef Paley likens the truffle hunt to foraging for morels, a mushroom with similarly elusive properties. “Once you find one, you find a whole field of them,” he says. “They reveal themselves to you.”

Czarnecki knows the cat-and-mouse game well. He forages for mushrooms at least once a month, an activity pursued since he was seven years old. “My father always describes himself as a mushroom hunter who likes to cook,” he says. (His father Jack, a celebrated chef, also wrote the James Beard Award–winning cookbook: A Cook's Book of Mushrooms).

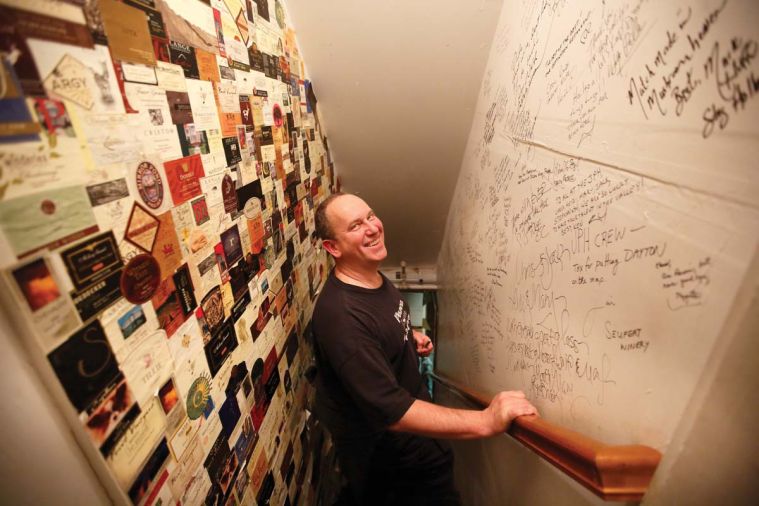

Most of the areas he and his father forage are on private property, where his family has long-standing relationships with the landowners. “They let us hunt truffles and we buy them dinner at the Joel Palmer House,” says Czarnecki. Who could resist such a deal?

Especially as the story of Oregon truffles unfurls. Historically, when gourmands would vet Oregon truffles against the famous French black (Perigord) and Italian whites from Alba, they looked down their nose at Oregon. Czarnecki attributes this to premature harvesting, when truffles are plucked before their maturation phase. Truffles fruit and ripen underground; when harvested too early, they lack their beguiling aromatics and have little culinary use. As local foragers and chefs learn the necessity of harvesting mature, ripe truffles— usually in the heart of winter, the perception of Oregon truffles is changing. One example of this is market value and demand, both of which continue to soar each year. In 2015, the market price for the Oregon winter white truffle is expected to reach $560/lb., up from $120/lb. a few years ago. The high price translates in the kitchen, where this indulgent ingredient dresses up dishes from risotto to ravioli, and elevates fare from satisfying to sublime.

Our quest for the heavenly taste continues, as the three of us, plus the truffle-dog-in-training, crest a hill, then scatter throughout the fir forest. “We could cover all the trees in this area, and not find one truffle,” says Czarnecki, “yet be standing just ten feet away from where they are actually growing.” This promise of discovery fuels us. Imagine if truffles frolic beneath the very ground we stand on. As Czarnecki sifts soil, he details how white truffles will roll right out of the earth with a few soft rakes. Although truffles grow underground, the white truffles, especially, are found very close to the surface, where the soil is looser. That’s one reason why the chef emphasizes the importance of delicate raking. When done lightly, raking aerates the soil, churning the decaying matter back into the ground. Vigorous raking can tear the roots from trees, destroying the truffle harvest for next year. “With foraging comes a responsibility and stewardship to the forest,” says Czarnecki.

Behind the clouds, the silvery light of autumn’s sun glints higher in the sky. Without rain, we trekked longer than planned, and the hours sailed by. For a moment, we stand in the lush forest, and it’s serenely quiet. The only sound is the rhythmic tip-tap of dew on the tree branches. Then Czarnecki shouts: Bingo! And he falls to the ground. And he digs. He rises to his knees, holding what looks like a small, dirt-covered potato between two fingers. Czarnecki sniffs; checking aroma first, next color, then firmness. “It’s a false truffle,” he says with lament. Even though the find was an imposter, both chefs are exhilarated.

What’s the secret? As we scrabble over to one last section of forest, it’s clear we are likely to return to the kitchen empty-handed. Yet, when we leave, we will continue to covet this strange and wonderful, sensual and sub-rosa ingredient. Is it the elusiveness that enhances its mystique?

“Isn’t it human nature,” says Paley, “to go after things that are hard to get?”

That answer satisfies until we drive back to the Joel Palmer House, where Czarnecki fortuitously has one black truffle on-hand. In the kitchen, both chefs whip up a dish—a classic oeufs brouillés à la truffe, and pasta with lobster. Each dish graced with chiffon-like slivers of Oregon black truffle. All it took was one bite from each plate. Little bites of heaven. And then the secret was revealed.